Rediscovering Sorley MacLean

October 27, 2011

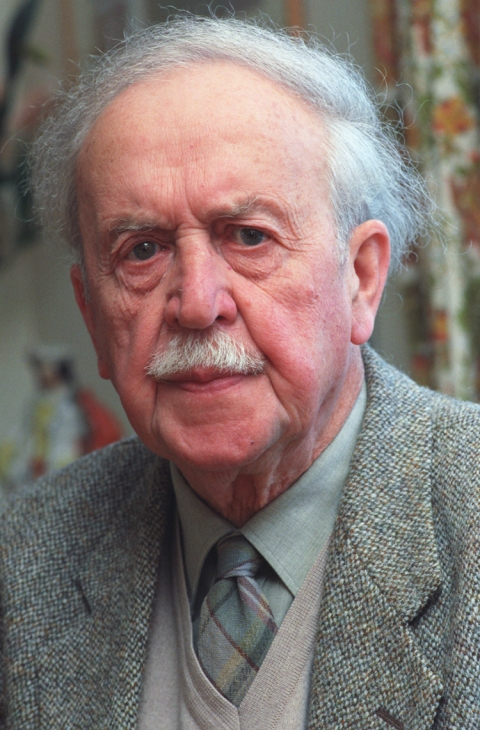

It’s a hundred since Sorley MacLean (Somhairle MacGill-Eain) was born at Osgaig on Raasay, off the Isle of Skye. Towards the end of his life, MacLean became recognised as the greatest Scottish Gaelic poet of the twentieth and perhaps of any century. His 1943 collection Dàin do Eimhir agus Dàin Eile (‘Poems to Eimhir and Other Poems’) revolutionised Gaelic verse, bringing it back into contact with the mainstream of European art and politics. While Gaelic poets had once taken this for granted, the marginalisation of Gaelic culture in the years following the sixteenth century had barred Gaelic speakers from participating as equals in the cultural and political life of the continent. MacLean’s poetry was a radical challenge to that exclusion.

At the heart of the 1943 volume were the ‘Dàin do Eimhir’ themselves, a group of love poems addressed to Eimhir, a mythical figure from early Gaelic literature. But intriguingly MacLean had left gaps in the numbered sequence, which had to wait until after his death to be published in full. The poems take as their backdrop the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War and enact the age-old conflict in European poetry between the competing demands of Love and War. MacLean’s speaker is torn between his love for Eimhir and his desire to join the International Brigades in their struggle against fascism. In the fourth poem he asks the question that underpins the sequence as a whole:

Dè gach cuach ded chual òr-bhuidh

ris gach bochdainn, àmhghar ’s dòrainn

a thig ’s a thàinig air sluagh na h-Eòrpa

bho Long nan Daoine gu daors’ a’ mhòr-shluaigh?What is each ringlet of your golden hair

when weighed against that poverty and fear

which Europe’s people bear and still must bear

from the first slave-ship to slavery entire?(Translation Iain Crichton Smith)

What was new here was the explicit connection between the plight of Gaelic speakers, here taken to be sold into slavery in the New World, and the fate of Europe as a whole. Echoing the Gaelic song tradition, MacLean takes advantage of the abundance of rhyme in his chosen language to bring his poem to a resounding perfect cadence in these lines. This was Gaelic verse deployed to a new and necessary purpose.

When I first read these wonderful poems, I was struck by that heady mix of erotic desire and political commitment. The unresolved tension that MacLean sustains throughout the sequence somehow makes his politics more passionate, his passion more urgent. But when they were first published, Gaelic readers were shocked by their difficulty and their dissonance, some going as far as denying they were Gaelic poems at all. The place the MacLean’s poetry has come to occupy in the Scottish poetic imagination – while richly deserved – has more to do with the persona the poet adopted in his later life, the weather-beaten representative of a dying culture who could safely be adopted by the Anglophone establishment without subjecting their hegemony to serious challenge, than with his remarkable poetry. MacLean’s acquiescence to the demand that Gaelic writers translate their work into English has damaged his own reputation – he thought his English versions ‘bald scarecrows’ compared to his Gaelic poems, and he was right – but it has also made it more difficult for those that have followed him to continue to develop Gaelic poetry on its own terms, without nervously looking over their shoulder to the expectations of an English-reading public. Today’s Gaelic poets still live in the shadow of Sorley MacLean. He negotiated a place for them in the Scottish literary scene infinitely narrower than that imagined in the ‘Dàin do Eimhir’, where Gaelic poets and musicians rub shoulders with Blok and Beethoven. This centenary year of MacLean’s birth will see the publication of new volumes of his work, with his long political poem, ‘An Cuilithionn (‘The Cuillin’) due to appear in its full original form for the first time. Now, like never before, we have a chance to rediscover Sorley MacLean’s poetry in all of its challenging beauty and complexity.

Niall O’Gallagher is a Gaelic poet and journalist. In 2009 he received a New Writers Award from the Scottish Book Trust / Gaelic Books Council. He lives in Glasgow. This piece was first published in our Poetry Reader issue 9.

October 27, 2011 at 4:47 pm

Thank you – it makes me sad I’m only reading the bald scarecrows. I hope this will change one day soon:-)

October 27, 2011 at 10:14 pm

[…] Scottish Poetry Library posted an awesome article about the man and if you haven’t discovered him already, this is a good introduction and if […]